Understanding the Definition Of Humane

Posted on November 22, 2016

It’s time to rethink the definition of “humane” when talking about scientific research and lab animals.

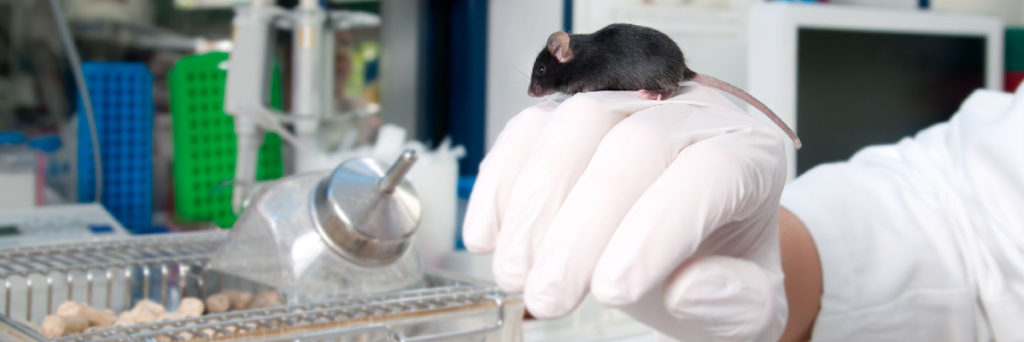

One of the most common critiques against animal testing is that the conditions are inadequate. In addition to being perceived as inhumane, opponents argue that poor conditions can alter important test results. Stress, in particular, can weaken an animal’s immune system. It can change their response to pain. It can cause an animal to exhibit behaviors that they would not under normal conditions.

The usual response from researchers is that they are already well aware of this. A bevy of laws and guidelines already dictate the care of laboratory animals. Housing for animals must meet certain criteria. Researchers must handle their animals in a manner that is not abusive. They would never purposefully violate the rules, as it would distort the integrity of their research.

So, what is the issue? The rules might be incomplete. Even in following them, researchers can create less-than-ideal conditions for their research animals.

Scientists Corrupting Results By Accident?

Olfactory Exposure To Males, Including Men, Causes Stress And Related Analgesia In Rodents, a study published in 2014, provides an example of exactly that.

It started as an anecdotal observation that mice seemed to exhibit a reduced response to pain when in the presence of male researcher. Seeking an explanation, researchers decided to delve further into the mystery.

Using “experimentally naive” mice, ones that had never been used in tests before, the researchers tested their responses to pain under various conditions. They found that exposure to men generated a “robust physiological stress response.” The heightened stress, they found, was changing how the mice reacted, even causing a stress-induced analgesia (pain reduction).

What’s more, researchers found that male researchers did not have to be present for this effect to occur. Mice can differentiate humans by smell, and the presence of “T-shirts worn by men, bedding material from gonadally intact and unfamiliar male mammals, and presentation of compounds secreted from the human axilla” could reproduce the effect to the same degree.

The level of stress was significant enough to cause mice to hug the walls of their enclosures, and even soil themselves in fear. The effect was greater in female mice than males and could be as significant as a 35-percent reduction in pain.

That’s more than enough to impact the results of any research significantly. Going back through data of previous behavioral studies, they learned that the sex of the experimenters altered the pain threshold of the mice and caused them to exhibit more anxiety than would have been present under normal conditions .

These researchers did not violate any rules regarding animal treatment in their initial studies. They had no intentions of exposing their mice to such heightened stress. Yet they did, simply because they couldn’t anticipate what the mice would interpret as being stressful.

A paper from Trends In Cancer, titled Thermoneutrality, Mice, And Cancer: A Heated Opinion, provides a more recent example of researchers inadvertently subjecting mice to unnecessary discomfort.

The paper notes that many labs house mice in “sub-thermoneutral” temperatures of 22 to 26 degrees Celsius. This is below what mice would consider comfortable, the “thermoneutral” range of 30 to 32 degrees Celsius.

What difference could a few degrees make? The paper posits that thermoregulation, the maintenance of core body temperature, requires “significant vascular, neural, and biochemical activity as well as conscious and unconscious behavioral adaptations.” The lab conditions that humans find standard cause mice to undergo chronic cold stress.

The cold stress, they reason, has unintended results in the physiology of lab mice. Because of their small size, they cannot grow enough extra fur or fat to compensate for heat loss. They must use a process called adaptive thermogenesis to cope.

A release of norepinephrine in the mice’s nervous system causes increased metabolic production. This allows them to adapt to the colder conditions but has several side-effects. They have to eat more, and they will implement behavioral strategies to conserve heat. These include building bigger nests and huddling together in greater numbers.

This, in turn, can result in “sedentary, obese and glucose intolerant” mice that have “great potential to confound data interpretation on outcomes of human studies.”

Again, this is not a conscious distortion of data. Indeed, The Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals recommends housing mice at sub-thermoneutral temperatures. Laboratory environments are under the discretion of lab workers. Though they are following the rules, the unintended consequence is consistent stress placed on mice that can warp experimental results.

What Can Researchers Do?

One step experimenters can take is to be more cognizant of the how small details can have a big impact. The aforementioned Guide already acknowledges that factors like temperature can have a profound effect:

“Exposure to wide temperature and humidity fluctuations or extremes may result in behavioral, physiologic, and morphologic changes, which might negatively affect animal well-being and research performance as well as outcomes of research protocols.”

The opinion paper referenced earlier recommends all studies report housing temperature as a variable that can effect results. Perhaps researchers can record other seemingly insignificant details to ensure accuracy and reproducibility in their studies?

It may also be time for scientists to update the conditions of their laboratories to reflect a new standard of what is humane. One institution, Oxford University, is already doing just that.

Oxford houses one of the foremost biomedical research centers. According to The Independent, they hold the distinction of performing more live animal tests than any other organization. They practice the “Three R’s” to limit the use of animal testing where possible but concede that some situations require the use of animals. In these cases, they seek to go above and beyond what most consider standard when providing a humane environment for animals.

In 2008, they completed a new facility, the Biomedical Sciences Building, to enhance the gold standard for animal care. The building, they claim, is “ultra-hygienic” in its design. It incorporates an advanced air cleaning system, modern health-screening practices, and full veterinary staff to monitor the welfare of their animals.

In addition, they have included “purpose built” housing spaces that allow social species to behave more naturally. This takes many forms, depending on the species in question, but all are geared toward keeping the animal environment clean and as close to normal as they can achieve.

Conclusion

This level of dedication should become the norm. The new standard of “humane,” if you will. As scientists learn more about how surroundings can affect animals, they must take every feasible effort to adapt their facilities to provide what is best for their animals.

Doing so will ensure the most humane animal environments possible, and make certain that research produced by studies in such facilities is more accurate and useful than ever before.